TOKYO, Jan 25, 2026, 22:22 (JST)

- Researchers report a distant quasar is accreting material at roughly 13 times the Eddington limit

- The object remains bright in both X-rays and radio, a combination that many models fail to predict

- Scientists believe there was a brief growth spurt in the early Universe

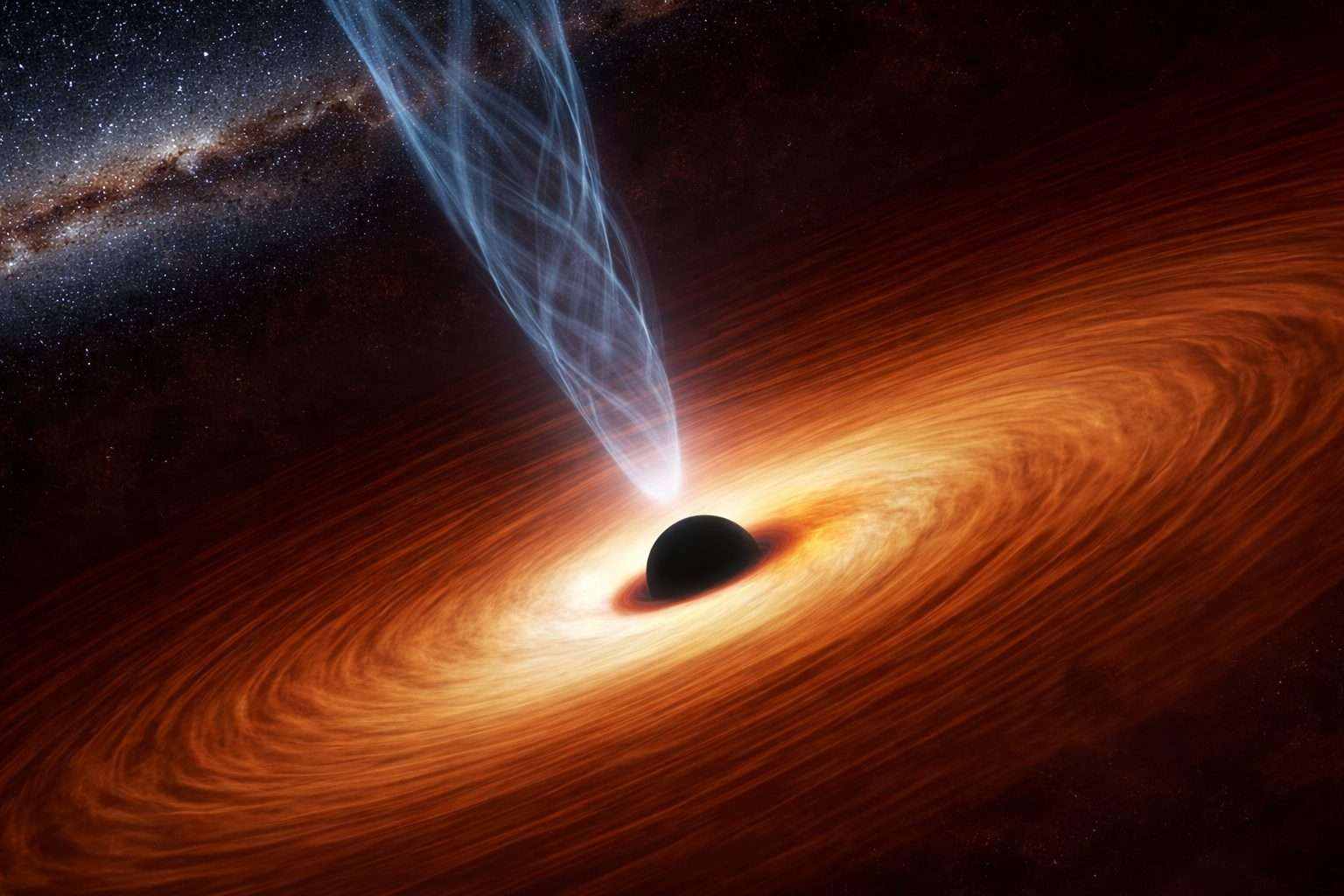

Astronomers have spotted a quasar—a luminous galactic core fueled by an actively feeding black hole—growing its central black hole at about 13 times the usual theoretical limit, yet still emitting strong X-rays and radio waves.

This pairing is crucial because it challenges common assumptions about how supermassive black holes feast on gas, and it fuels the ongoing debate over how these giants grew so massive so quickly.

Most galaxies harbor supermassive black holes at their cores, yet some appear in the early Universe growing unusually fast. The usual “steady” growth models can’t always explain the numbers.

One potential way out is “super-Eddington” accretion, where a black hole briefly sucks in matter faster than the Eddington limit—the threshold where radiation pressure normally halts further gas inflow. What makes this new quasar unusual is that it seems to surpass that limit yet doesn’t dim at other wavelengths.

The object, named eFEDS J084222.9+001000, dates back about 12 billion years, according to data collected by Japan’s Subaru Telescope. 1

Researchers examining extreme accretion often anticipate trade-offs. Many models predict that during super-Eddington phases, the inner flow shifts, dimming the X-ray emission from the hot plasma “corona” close to the black hole and reducing the strength of jets.

The new data reveal bright X-rays coinciding with intense radio emissions tied to a jet. Sakiko Obuchi from Waseda University, the study’s lead author, said the team aims “to investigate what powers the unusually strong X-ray and radio emissions,” according to a summary by ScienceDaily. 2

Using Subaru’s near-infrared spectrograph MOIRCS, the team analyzed the Mg II emission line—a spectral marker from magnesium—to gauge the black hole’s mass. They derived the accretion rate through X-ray data and detailed their findings in a paper published in The Astrophysical Journal.

The team suggested the system might be stuck in a brief transitional phase, likely following a rapid influx of gas. In this scenario, the black hole briefly enters a super-Eddington feeding state, keeping the corona and jet active until the system stabilizes.

The jet might also impact the host galaxy. Powerful jets inject energy into nearby gas, heating it or displacing it, which can change how readily the galaxy forms new stars.

Additional findings have complicated the bigger picture. Tech Explorist highlighted recent James Webb Space Telescope data backing the presence of active galactic nuclei in earlier epochs. Obuchi suggested the discovery might “help elucidate the formation process of supermassive black holes” in the early Universe. 3

But the “caught-in-transition” explanation comes with a catch: it depends on a fleeting phase that’s tricky to observe, and we still don’t know how widespread these systems really are. Researchers are digging through survey data now, hunting for more examples to figure out if this is a rare anomaly or a key to understanding early black-hole growth.