WASHINGTON, Jan 28, 2026, 12:27 EST

- Researchers supported by NASA identified a potential rocky planet, a bit bigger than Earth, orbiting a nearby star using data from Kepler’s K2 mission.

- HD 137010 b completes an orbit roughly every year but receives under a third of the sunlight that Earth does.

- The signal was detected from just one transit and requires additional observations before confirming it as a planet.

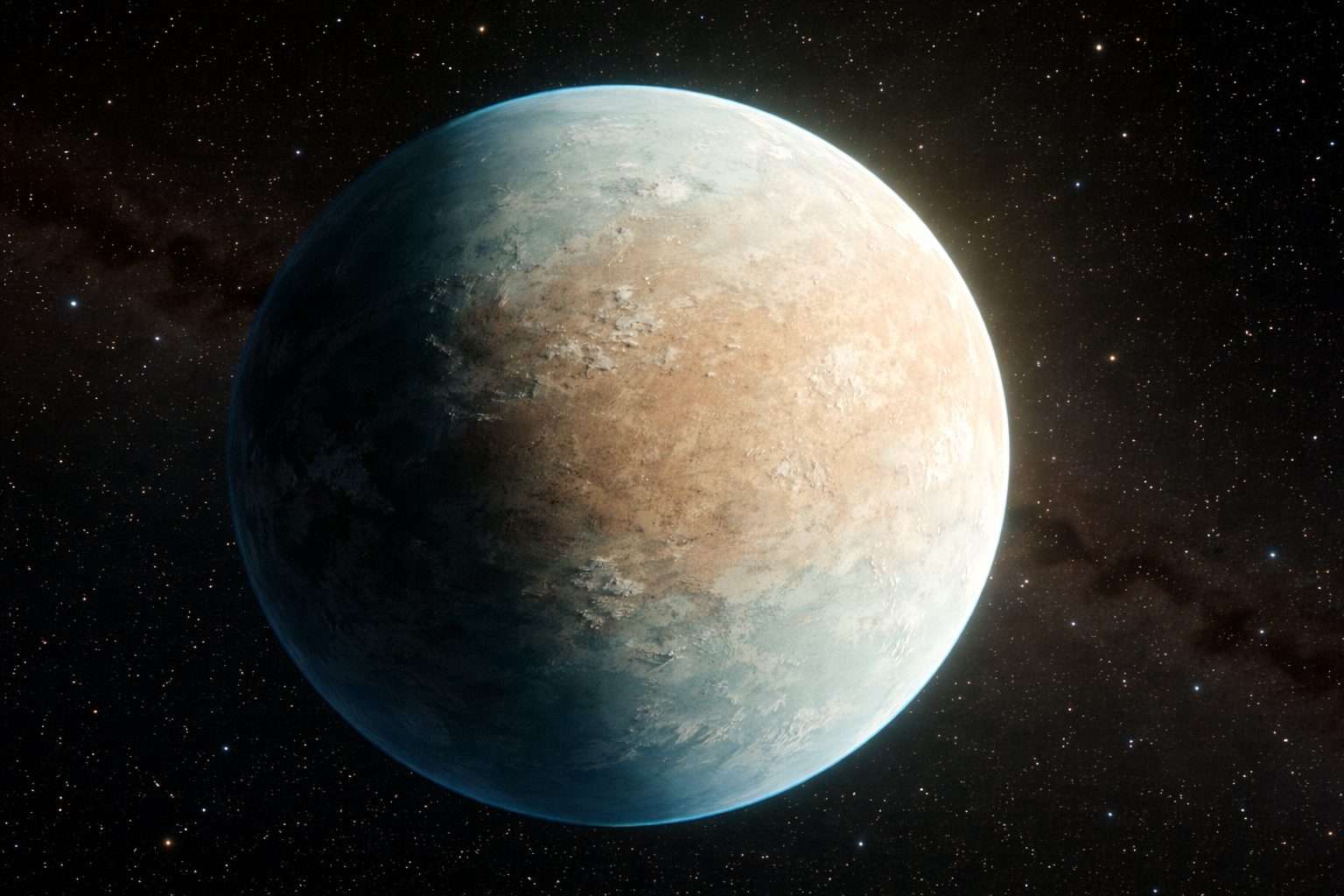

NASA scientists, together with an international team, have uncovered an Earth-sized exoplanet candidate while combing through data from the now-retired Kepler Space Telescope. This discovery might provide a rare opportunity to examine a long-period, near-Earth-size planet orbiting a relatively bright star nearby. Called HD 137010 b, the planet orbits near the outer edge of its star’s habitable zone — that’s the area where liquid water could potentially exist with the right atmosphere — though it’s likely colder than Mars. (Nasa)

Timing is crucial since planets with orbits close to Earth’s year are tough to spot using Kepler’s main method: tracking repeated dips in starlight. Missing just one transit could force a wait of a year or longer for the next chance.

The researchers described the signal as “a 10-hour long single transit event” in their report, adding, “To our knowledge this is the smallest planet candidate detected from a single transit around a Sun-like star.” From that single event, they estimated the planet’s radius to be close to Earth’s and its orbital period around a year, though the margin of error is still significant. (Arxiv)

NASA reported that the candidate orbits a star roughly 146 light-years from Earth. It likely receives less than a third of the heat and light that Earth gets from the Sun, which could keep surface temperatures around minus 90 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 68 degrees Celsius). By comparison, Mars averages about minus 85 F (minus 65 C).

The team spotted the candidate in data from Kepler’s K2 mission, employing the “transit” method — detecting a slight dip in a star’s brightness as a planet passes in front. NASA noted the event lasted around 10 hours, compared to Earth’s roughly 13-hour transit across the Sun.

One transit alone doesn’t cut it. Astronomers usually require multiple transits or additional data, like radial velocity measurements that track a star’s tiny wobble from an orbiting planet, to eliminate false positives from eclipsing stars or other interference.

NASA noted that confirming the finding might require additional observations from TESS, its active planet-hunting satellite, or from Europe’s CHEOPS mission. The problem? The planet’s nearly year-long orbit means repeat transits are rare and easy to overlook.

Published on Jan. 27 in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, the study was led by Alexander Venner of the University of Southern Queensland, now with the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, according to a report by Phys.org. (Phys)

The researchers also simulated the planet’s environment assuming it retains a thick atmosphere. NASA reported the team estimated a 40% chance the planet lies within a “conservative” habitable zone, 51% chance it’s in a wider “optimistic” zone, and about a 50-50 shot it’s outside the habitable zone altogether.

That uncertainty is the main risk behind the claim. The signal might turn out to be a false positive. Even if the planet exists, “habitable zone” only refers to its orbital distance, not actual habitability. The planet’s atmosphere and composition remain unknown.

Kepler, which ceased operations in 2018, transformed exoplanet research by detecting thousands of planets via repeated transits. This new candidate highlights the vast untapped data in the archive—and just how uncommon it is to find an Earth-sized planet with an orbital period close to a year that’s bright enough for follow-up observations.