WASHINGTON, Jan 22, 2026, 13:54 EST

- Data from Webb reveal crystalline silicates forming close to the young protostar EC 53 during its regular bursts.

- The Nature study connects these crystals to “accretion bursts,” brief episodes when a young star rapidly swallows extra material from its disk.

- Researchers noted they never directly observed the grains making it to the outer disk, the region where comets typically form.

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope detected heat-formed crystals close to a young star similar to our Sun and found evidence these crystals are drifting toward the chilly edges of its planet-forming disk, shedding fresh light on the comet mystery.

Crystalline silicates require intense heat to form, but comets in our solar system mostly linger in frigid zones far from the Sun. This new research links the crystals to the scorching inner region of a young system and to winds capable of pushing them outward—an essential piece for models explaining the mix of hot and cold materials.

Researchers analyzed Webb’s mid-infrared spectra—light broken into wavelengths that expose the chemical signatures of minerals—captured before and during a protostar outburst, the study published in Nature on Jan 21 revealed. 1

Webb’s Mid-Infrared Instrument, known as MIRI, collected two sets of observations, enabling the team to chart the mineral distribution within the disk, NASA reported. The findings suggest crystals form in the blazing hot inner zone, at distances comparable to those between the Sun and Earth in our own solar system.

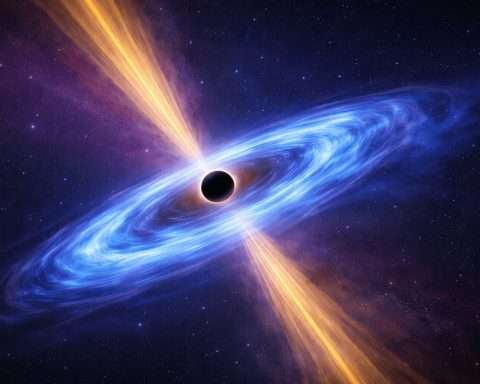

Jeong-Eun Lee, lead author and professor at Seoul National University, described the system’s outflows as a “cosmic highway” ferrying fresh crystals. Webb’s before-and-after images reveal precisely where this material settles during bursts. 2

EC 53 has been under observation for decades, and NASA notes it flares on a predictable schedule unlike many young stars. Roughly every 18 months, it kicks off a burst phase lasting about 100 days, during which it rapidly consumes gas and dust from its surrounding disk, then ejects some of that material in jets and winds.

The paper noted that the crystal signatures—tied to silicates called forsterite and enstatite—show up only during the burst, indicating rapid crystallization as the inner disk heats past roughly 900 kelvin. This heat-triggered transformation, known as thermal annealing, effectively “bakes” the dust into a stable crystal form.

Doug Johnstone, co-author from Canada’s National Research Council, called the discoveries “common minerals on Earth,” emphasizing Webb’s ability to detect specific silicates out in space. While crystalline silicates have been spotted in comets and near older stars, scientists had trouble figuring out their formation and movement until now.

The study revealed a nested outflow: a fast, narrow atomic jet encased within slower molecular flows. This fits models where magnetic fields launch winds from the disk. Joel Green, an instrument scientist at the Space Telescope Science Institute, noted that Webb can follow dust grains “smaller than a grain of sand” as the system churns.

But the Nature authors didn’t directly observe grains moving to the outer disk. Instead, they highlighted patterns that suggest outward redistribution. EC 53’s regular cycle makes it a simpler case; systems with chaotic or century-spanning eruptions would be much tougher to track through a repeating sequence.

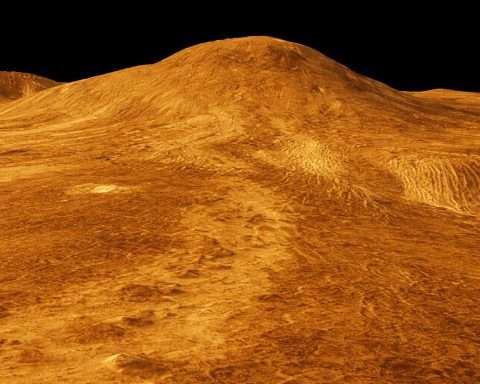

NASA reported that EC 53 is located in the Serpens Nebula, roughly 1,300 light-years away from Earth. The protostar could stay cloaked in dust for up to 100,000 more years before its disk clears and any forming planets become visible.

On January 21, the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore announced that these before-and-after images allow scientists to chart jets, outflows, and winds, pinpointing where the crystals might be traveling—sometimes all the way to the system’s outer edge. 3

Webb is an international effort spearheaded by NASA alongside the European Space Agency and the Canadian Space Agency. Scientists rely on it to observe star and planet formation as it happens — chaotic, luminous, and dynamic.