WASHINGTON, Feb 10, 2026, 09:39 (EST)

- Scientists report that reprocessing Magellan radar data has revealed the first-ever subsurface feature detected on Venus: a vast hollow lava tube.

- The study estimates a cavity beneath the Nyx Mons volcano region measuring roughly 1 km (0.6 mile) wide and at least 375 meters (about a quarter-mile) tall.

- Researchers say upcoming radar missions to Venus could put this finding to the test and search for additional underground conduits.

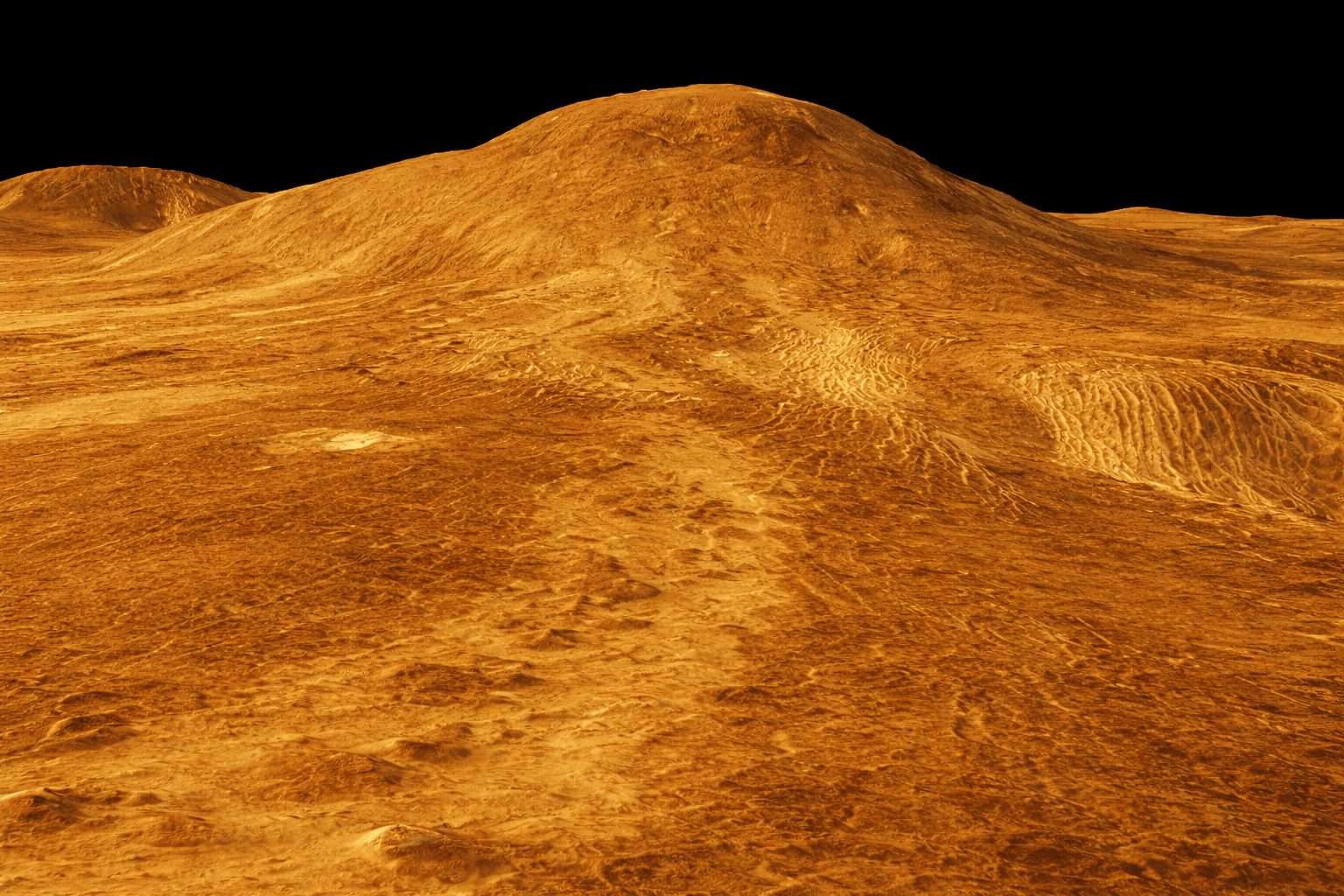

Scientists reexamining radar data from NASA’s Magellan mission have uncovered what appears to be a massive underground lava tube on Venus. This marks the first time a subsurface formation has been identified on the planet. Reuters

Timing is critical since Venus remains mostly a radar-mapped planet. Its dense clouds prevent regular cameras from seeing through, pushing space agencies to gear up for a fresh wave of Venus missions that will rely on advanced radar to chart the planet’s battered surface and surroundings.

The study also highlights how outdated mission archives can still cause headaches. Magellan flew in the early 1990s, yet the team applied updated processing techniques aimed at detecting the specific radar echoes a void might reflect.

Scientists at the University of Trento in Italy led the team analyzing Magellan synthetic aperture radar (SAR) images from 1990 to 1992. SAR leverages the movement of a spacecraft to create more detailed radar images than a single “snapshot” could capture.

They hunted for areas where the surface appeared to have slumped or collapsed—a typical sign of lava tubes on Earth. Their top suspect is on the western side of Nyx Mons, a wide, gently sloping “shield volcano” roughly 362 km (225 miles) across in Venus’s northern hemisphere.

The paper details a collapse “skylight”—a hole formed where the roof has collapsed—that seems to expose an empty conduit below. The team estimates the tube’s average diameter at roughly 1 km, with a roof thickness near 150 meters (around 490 feet) and an internal cavity height of approximately 375 meters (about 1,230 feet).

Magellan’s resolution restricts what can be directly measured, and the authors note the clearest data comes from the area nearest the skylight. Still, by tracking the winding series of collapse features, they estimate the underground conduit may extend at least 45 km (28 miles), including a stretch with no clear surface cracks. Nature

“Moving from theory to direct observation marks a major step forward,” said Lorenzo Bruzzone, a radar and planetary scientist at the University of Trento and senior author of the study. Leonardo Carrer, the study’s lead author, noted, “Our knowledge of Venus is still limited,” describing the next decade as “pivotal” for Venus research.

Lava tubes develop as hot, fluid basaltic lava flows beneath a cooled, hardened crust, creating tunnels once the lava drains out. These formations appear in volcanic areas on Earth, have been spotted on the moon, and are believed to exist on Mars as well.

The researchers suggest Venus’s environment might support the formation of large lava tubes. Thanks to lower gravity and a thick atmosphere, lava could develop a solid insulating crust quickly, which may encourage the growth of extensive tube-fed channels, Bruzzone explained. He also noted the team can only “confirm and measure” the section near the skylight so far; new radar data will be crucial to determine the conduit’s full length. Phys

The case isn’t settled yet. The study explores other potential causes for pits and chains, such as tectonic voids or collapses linked to subsurface dykes—magma intrusions—and notes that some uncertainty persists without clearer images and better subsurface data.

This is where the next wave of spacecraft steps up. The European Space Agency’s EnVision and NASA’s VERITAS missions will carry higher-resolution radar systems. EnVision, in particular, will feature an orbital ground-penetrating radar capable of probing hundreds of meters beneath the surface—potentially confirming the void and uncovering others.

Bruzzone pointed out that a lava tube alone wouldn’t confirm active volcanism on Venus. But recent research has hinted that some volcanoes there might still be alive — which, Carrer added, gives the next decade a real shot at uncovering what’s hidden beneath those thick clouds.